Most music lovers want to go beyond a band’s greatest hits — that’s often where the hidden gems are found. The same can be said for art from the Middle Ages.

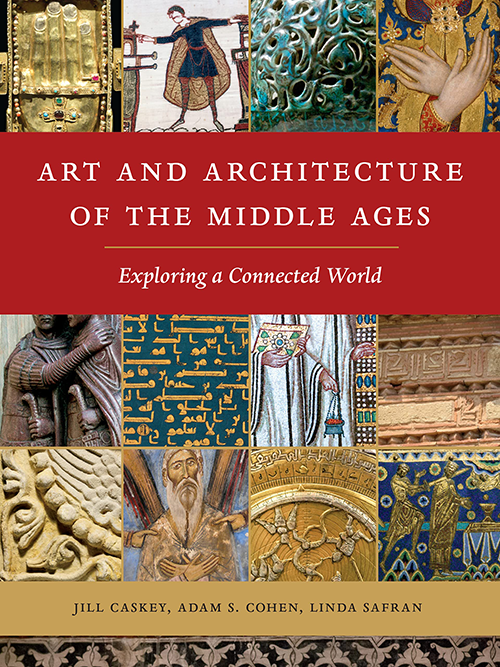

Adam S. Cohen, an associate professor in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Art History, has joined professors Jill Caskey of the Department of Visual Studies at U of T Mississauga and Linda Safran of the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, to create the textbook Art and Architecture of the Middle Ages: Exploring a Connected World.

“It stemmed from frustration with what was out there that represented traditional ways of presenting the art and architecture of the Middle Ages,” says Cohen. “We thought what was needed was to make this already exciting subject even more compelling to students today.”

Released last month, the book shows students a much broader diversity of places and peoples in the medieval world, as well as a greater variety of works — moving well beyond cathedrals and castles.

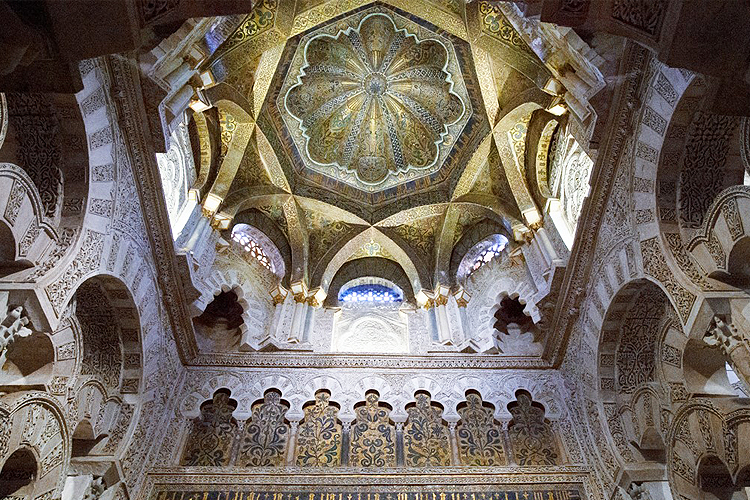

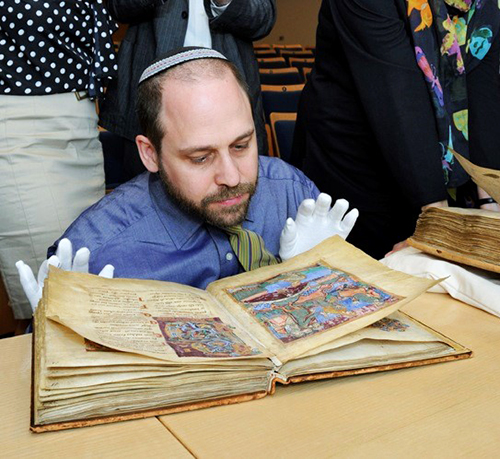

Spanning over 12 centuries of artistic creation from about 300 to 1400 CE, and covering Europe, western Asia and North Africa, the book is 400 pages with over 450 colour illustrations of sculptures, pottery, manuscripts, textiles, paintings and buildings. The artifacts are of both a religious and secular nature, covering several faiths, including Zoroastrian, Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions.

“For myself, I thought I should be teaching Islamic art within the presentation of medieval art. So I wanted a textbook that I could use for my own classes that would be more global, more inclusive

“For myself, I thought I should be teaching Islamic art within the presentation of medieval art,” says Cohen. “So I wanted a textbook that I could use for my own classes that would be more global, more inclusive.”

Cohen, Caskey and Safran worked on this book for six years which involved countless hours of research, collecting images, photographing artifacts, as well as commissioning architectural drawings and maps (made by U of T graduate students).

The result is a wide spectrum of objects and art that paints a more realistic picture of people’s daily lives and activities.

“Textbooks in any field tend to reproduce the traditional roster of great monuments, and they get trotted out year after year,” says Cohen. “We wanted to respect that tradition in our discipline so that many of the greatest hits would still be there.

“But we also wanted to shake it up a little and put in new things — things people didn't traditionally look at that reflect the experience and the built environment of people in the Middle Ages. Depending on where you lived, you only saw great cathedrals once or twice in your life. That's not what most people experienced. So we wanted to broaden the field and show more of what was out there at the time, more everyday things.”

In addition to the images, the book’s introduction provides helpful context to better understand the artifacts’ relevance and meaning.

“We tried to lay out some concepts about the different approaches we use in looking at any object in the history of art,” says Cohen. “What's represented? What's the style? Who was responsible for the thing looking the way it did? How was it received? What was the audience? If it's on the altar in a French church, that's one audience, if it's a bath house in Jordan, that's a very different audience.”

As well, each chapter also offers a more detailed description of two artifacts.

“For example, we look at a 13th century French church and say, ‘This is what some of the images represent. This is what the patron was trying to get at in rebuilding his church. These are some of the stylistic changes that were introduced at this particular church that would go on to have great currency in medieval France. Here's some of the experiences that pilgrims would have had when they came to that church.

Now we feel like we've got a textbook that introduces students to the material in a responsible way that reflects our concerns in the 21st century, not the concerns that were shaped in the 1950s and ‘60s.

“We hope that doing this twice per chapter will remind people that every object could be treated at this depth, because each object has so many layers.”

To complement the book, Cohen and his co-authors also created a dynamic website that extends the book’s materials even further. It includes resources such as a glossary, maps, timelines, photo essays, and a podcast “Medieval Art Matters,” where medieval art and architecture experts share their insights and expertise.

“The website is a way to amplify what we show,” says Cohen. “We know that students still like a traditional textbook, but books have limitations — you can only have so many pages and so many pictures.

“And we could start doing additional things like text translations, things that couldn't be captured in a book effectively. It’s an opportunity to go bigger in different directions.”

Cohen can’t wait to use this book in his classes when he returns from sabbatical in 2024. But his co-editors will be cracking it open with their classes this month.

“Now we feel like we've got a textbook that introduces students to the material in a responsible way that reflects our concerns in the 21st century, not the concerns that were shaped in the 1950s and ‘60s.”

The book's website complements the book rather than duplicating it; it features galleries of medieval objects, buildings, and cities, selected for their relevance to contemporary interests and events, such as recent discoveries or interpretations.

Each work is discussed and tagged in ways that will support classroom projects and student research, while also fostering interest in the field.

Some features focus on pedagogy: plans, maps, timelines, glossary and translated primary sources, while others — such as the podcast series Medieval Art Matters — illuminate connections between medieval art and real-world professional practitioners.